Pátek 05/2015

GENES OF DESIGN

World-famous designer and artist ARIK LEVY on business on the beach, hard work, long-term success and bending Czech wood

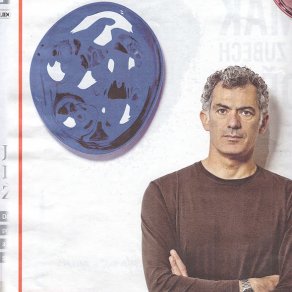

For a beach bum, as he characterises himself, he has gone far. Even though he denies it and repeats that we should look at the product and not at him, Arik Levy is a top global designer. And it is worth taking a look at him. The course of his life is very inspiring.

He originally made a living with design in order to afford sculpting and painting to which he was devoted. He could not support himself as a young artist in his native Tel Aviv, and thus he relied on his other passion and spray painted and stained surf boards for people and eventually designed logos. In life he naturally proceeded according to an interesting model, following his desire regardless of how much he would have to slave away at it.

The fact that today he is a globally recognised designer and artist that prestigious galleries and luxury brands curry favour with is rooted in the hard work and naïve courage at the beginning of his career, as is made apparent in this interview. He now lives in Paris, where he has led the renowned L Design studio for more than two decades now.

In the Prague Kabinet gallery and shop, where an exhibit of Arik Levy’s artworks is currently ongoing, Levy’s sculptures appear against the snow-white space as shining bronze stalagmites. We sit among them, but we are discussing his design work. Levy is frequently in the Czech Republic these days due to his collaboration with the companies Lasvit, Bomma and TON. And in their case, he uses the same thought process, trying out some untested properties of materials. And there are always his clever and amusing items, such as a chair painted like a surfboard.

You say that you love the sun and the beach. Why don’t you return to Tel Aviv?

Tel Aviv is a city with great energy. But how could I return? Setting aside the fact that the country is at war, it is more difficult to travel and work from there. Flying from Paris to Prague takes an hour; it is much farther from Tel Aviv. If I want to go to Milan, I simply get up in the morning and I’m home for dinner. I travel so much, roughly fifty business trips every year, that if I still flew from Tel Aviv, I would not see my family at all. From Tel Aviv, I would travel one day, spend a day in the destination and go back on the third day. If you have children, you think about where you settle down. But I go there to visit my family three times a year. My 101-year-old grandmother is there.

Is your grandmother originally from Bulgaria like your grandfather?

All of my grandparents, from my father’s and mother’s sides, come from Bulgaria, from Sofia. My grandfather on my mother’s side owned an appliance shop in Israel. He had there an enormous cabinet radio with round knobs. For me, that was just like Alice in Wonderland. My other grandfather was a chemist specialising in plastics and rubber. So, one was a merchant and the other was a scientist. Both of them inspired me immensely. I visited my shopkeeper grandfather every Friday and he would tell me that if I came up with my own invention, I would get a present from him, so I was always building something. He was very strict with everything. Education at school was a disaster for me because I am severely dyslectic. It is difficult for me to read and write. I grasp languages easily, so I know French well, but I am not able to write in French.

By the way, do you speak Bulgarian?

No. Jews in Bulgaria spoke the ladino dialect; they spoke Bulgarian only when they wanted us children not to understand. After moving to Israel, my grandparents had the same attitude as other surviving Jews, so they never spoke Bulgarian or ladino to us. My mother’s parents left Bulgaria for what would later be Israel in the 1920s, so my mother was born in Israel. My father was born in Bulgaria, but he has never wanted to go back there. My grandfather the chemist had a rubber factory in Bulgaria. He was in a concentration camp during the war. The communists came in 1954 and took the factory from him, perhaps in the same way as nationalisation here. They offered to let him continue to work there but he packed up and left for Israel with his family the next day.

Do you recall from your childhood any typical Bulgarian furniture that they brought with them? And their taste?

Their taste, yes; but not the furniture. At the time, I didn’t pay attention to that. But one of my photographic works is a collection of photographs of my grandmother’s flat. It’s full of old furniture. In Israel, no one had money at the times they were young, so still to this day my parents do not throw away furniture just because it is old. We simply repair and refinish it. My mother has had the same shelves for forty years. My grandmother had a couch reupholstered until it was as stiff as a board because of all the layers.

Did that influence you as a designer? Do you recycle old things or create only new ones?

Neither of those. I choose parts and details from the past and bring them into the future. By adding to them something from the genes of Arik Levy, I change their DNA. I don’t want to make vintage; that doesn’t interest me. The chairs that I design and those that we are sitting on now will be vintage in fifty years. The question is whether that chair will survive and become an icon of its era. That will happen only if you invest some knowledge of the past and a vision of the future in it. It works in such a way that when you look at a new product, you should have the impression that it is familiar to you.

When did you perceive that something such as design exists?

Some time in secondary school. But I began with painting and sculpting much sooner. After three years of military service, I wanted to study art and dedicate myself to that. After the vernissage of an exhibit of my sculptures in 1986, which was great, my father asked me how I planned to feed my children some day. How could I buy them chicken with this hobby? At that time, the art trade worked much differently than it does today. Even a Picasso cost only some two hundred thousand dollars, perhaps not even that much. I also had the problem of what to do with the sculptures and paintings after an exhibition. In Europe, there was a class of intellectuals who knew from their parents that art is to be purchased, but in Israel most people simply worked hard to survive. They went to a museum for art. So when I told my father with his wartime and post-war experience that I wanted to make ark, he didn’t understand at all. “Why don’t you go to work somewhere in a supermarket?” he would ask.

So how did you make a living?

I realised relatively soon that it wouldn’t happen with art. I looked for a way to make a living and, at the same time, to do something that I enjoyed. I started a fine business on the beach and I soon owned three stores and three rental shops for surfing and windsurfing gear. I’m really a beach bum. With a spray gun, I started to stain and paint surfboards. I painted two thousand of them. If I had painted on canvas back then, I would have two thousand pictures under my belt. It was great, people came to have their boards painted only by me. At the same time, I opened a graphics studio. I was an autodidact; I didn’t learn anything at school. I didn’t know how a print shop operated, for example, so I basically moved in, slept there, pestered people to teach me as much as possible, how colours are separated, how a letter is composed. There were no computers back then; I composed letter by letter. Today, when design-school graduates come to me at the studio, I ask them if they know how printing works. You just simply send a file. I ask them to whom they send it. Well, you send a PDF to the print shop. And have you ever been to a print shop? No. So I buy them a gift of a lifetime, a train ticket so they can go have a look around a print shop. They come back wide-eyed. In my studio, I gradually began to do product design, letterheads, logos, corporate identity. So I made money with design, which I invested in my art.

“When I told my father with his wartime and post-war experience that I wanted to make art, he didn’t understand at all. ‘Why don’t you go to work somewhere in a supermarket?’ he would ask.

But you eventually abandoned that?

My girlfriend left to study in Switzerland and I wanted to be with her. So I sold everything in Israel. I was twenty-eight. Again, my father didn’t understand: “Have you lost your mind?” But I simply woke up one day and said to myself that I didn’t want to be without her, so I called her and told her that I would be there in two weeks and then I immediately went to a travel agency and told them that I wanted a one-way ticket to Geneva. In order to be with her there, I had to study, so I looked for an art school, even though I was under the impression that I didn’t have anything more to learn. I went there for a while, but I found it boring. Then I heard about the Art Centre College of Design in California, which at that time had opened its Art Centre Europe branch in Switzerland. So I quickly got my portfolio together, gathered up all the money that I had saved, including money from my bar mitzvah and flower delivery, my girlfriend took my application and my work to the school and in two weeks I received a letter telling me that I had been accepted. That was a great school. I learned a lot of things about materials, technologies… But it was a mad experience.

Mad in what way?

I spoke basic English. My schoolmates were much younger; I was twenty-eight and I had spent three years in the military, so I had the impression that I was three times older than them and that I had three times as much life experience. They didn’t know how to make an omelette, and I had had my own stores and a studio. But every one of them spoke four or five languages fluently and freely switched from one to another. I felt like I was from the developing world. I had to study extremely hard, because I didn’t take the tests at first, so I got up at five o’clock every morning, even during the summer, because I didn’t have any summer holidays. I sat on a train and travelled an hour and a half from Geneva to the opposite side of the lake, where the school was located. I came home at eleven o’clock in the evening, because after the standard lectures I took classes in physics, English and art history. Who in Israel had ever heard of art history? I didn’t know anything about it. One of the tests was a slide show of a hundred artworks where the student had to state the artist and the title and the year of creation of the work. On average, my schoolmates got seventy percent, because they grew up with this knowledge. I recognised maybe three works and I still didn’t know who the artist was. But I dug into and studied as if I were studying for my life. Over two and half years I travelled 93,000 kilometres on the train. I made and painted models of products for the product-design class in the train lavatory. I finished school with honours. Then we decided to move to Paris. Again, I didn’t know the language, just “Bonjour, je m’appelle Arik.”

You repeatedly throw yourself into the deep end.

I like it that way. The reward is that I make a living doing something that I am passionate about.

Wasn’t there a line of similarly talented artists ahead of you in Paris?

Yes. But I have good social skills. Without knowing French, I started to teach at a school part-time. I had all the documents in a good order thanks to that school, so I could live in Paris. Then one gallery owner offered to exhibit my works. I thought that it was just a nice thing to say, but she really organised an exhibit of luminous sculpture. Today she is like my Parisian grandmother.

When did you realise that you were in the first league of designers?

I don’t think that I’m famous; I think that I am known. I don’t belong among the trendy, popular designers. I am a very bad decorator. My things have a long lifespan; they are not fashionable and it isn’t easy to embrace them. So Levy’s things will last longer than they sell. I’m not, for example, Marcel Wanders; that is a real design star. Such famous designers also work with fame. I’m interested in what I do and the relationship with the people with whom I do it. The stars know how to easily connect with what interests and amuses people. I don’t know how to do that. I’m interested in materials. I have eight different products that I designed for the well-known glass company Baccarat; I think all of them are beautiful and have a long life ahead of them. I once slept for a week in a glass company. I had a key to everything, I had breakfast with the local glassmakers. That’s how I like it. I want to close my eyes and recognise the sound that the machine makes. The success of my things will also build over time.

Your name serves as a brand for manufacturers. Is that right?

Yes, that I know. But it doesn’t work in such a way that when you have the name Arik Levy in your collection, your sales will multiply. I think that the name Arik Levy can mean that a manufacturer is interesting and capable of evolution and that in years to come it will be about substantial things, not something that will just fill magazines. Maybe in ten years you will recall what I did, but do you remember what Philippe Starck did ten years ago? He is great and he beat a new path for design, but every six months or so he throws away the things that he did before; it has to be different every time, and what came before is gone. A lot of designers do that and it’s not their fault; it’s just how the industry works.

Doesn’t it seem to you that everything is a bit overdesigned? In the past decade, everything has revolved around design.

It’s true that the word “design” has lost its clear, primary meaning and has taken on a lot of others. They sell designer toothbrushes and designer toothpaste at the supermarket today. Twenty years ago, if you asked someone what he does, he would say: industrial designer. And you would know exactly what he does. Today, he will tell you that he’s a designer. Aha. And what does he do? It’s hard to say. Today there is product design, automobile design, graphics, cultural, interior design, everything design. But design schools are not evolving to such an extent. Seventy percent of the graduates they turn out are neither designers nor artists.

Why not?

They don’t have the necessary passion; they often only want to have a Mac computer, make something cool and travel to Milan. The teachers in design schools should be so responsible that they can tell students: “You are not a designer; study something else.” For example, design management, because a lot of designers don’t know how to sell their work or contact manufacturers. When I was studying, whoever didn’t work hard and didn’t give everything to his studies got kicked out; we always had knots in our stomach before every final exam. Today it’s enough to show up for school and everything is fine. When I get invited to sit on a committee as an external assessor, ninety percent of the people don’t pass. So they stopped inviting me to participate in the committees. But if they don’t say that to a student immediately, then that student will be disappointed for the rest of his life because he can’t get a proper job. Hundreds of interns pass through my studio, so I see how they are.

Designers also bear responsibility, for the environment for example…

That is a huge responsibility. It’s enough to reduce the size of packaging by a millimetre and multiply that by twenty million and that’s a lot of trees. It’s good that ecology and caring about the world are no longer considered to be extreme or crazy; it’s part of the mainstream now. I tell my employees and students to always think about whether they can do things more efficiently, if they can save energy somehow. I make sure that they pick screws up off the floor and put them back in the box if they can be used again and that they cut cardboard efficiently so as to throw away as little as possible. But customers also have great responsibility for which way the design will go. If you go to buy a chair, you try it out and it’s not comfortable, so you don’t buy it, even if it was designed by some star designer. Today people buy chairs on the internet because they’ve seen them ten times in a magazine without ever trying them out to see if they’re comfortable.

You have been much talked about among Czech manufacturers lately. You have collaborated with companies such as Lasvit, Bomma and now TON. How did you end up here?

I did the first thing for the glass company Květná. I was invited by Tereza Brthansová, who at the time was the deputy editor-in-chief of the magazine Dolce Vita and has a very knowledgeable and critical eye. She wanted to somehow motivate Czech manufacturers. I already had experience with glass from working with Baccarat, so I was interested in how they work with crystal in the Czech Republic. I’m currently making my bronze sculptures here. I looked for high-quality specialists in bronze in France, but I found them here. My guy doesn’t speak a word of English; his wife translates everything but he understands exactly what I want. He is careful and motivated. I’ve had nothing but good experiences here, so I come back five or six times a year.

How did you get involved with TON?

Michal Froněk from the Olgoj Chorchoj studio got us together, the idea being that we would be right for each other. Not because Arik would be trendy, but because he works slowly and his things have a long lifespan. In industry the illusion persists that a famous name sells, but that was true in the 1990s, not today. So I advise manufacturers not to put my name on the product.

Perhaps they’re not too happy about that.

It’s hard for them, because they’re used to doing that. But the name doesn’t make the product. It’s the product that makes the name. If you put the name on a bad product, it still won’t sell. I want to believe, I hope, that we live in a world where we understand what is important and what is only flash and image. Besides that, it can happen to manufacturers who place too much emphasis on my name that they end up working for me instead of for themselves. My Wireflow light fixtures for the Vibia brand are selling very well, they are very nice, and that has nothing to do with my name or with the Vibia name. And if I were to hypothetically start designing for Thonet based on the TON example, then at TON they should say to themselves, “let them do what they want; we have a great product.”

Were you aware of the legendary chair no. 14?

Of course, but I didn’t know anything about TON or Thonet. I heard about TON from Michael Froněk. The company’s director, Milan Dostalík, came to Paris first. He’s got both feet on the ground, very direct, which I like. I told him that I didn’t want to make chairs. I wanted to do a collection that would convey a single idea. And that idea had to please both him and me. Which is the opposite of let’s make an Arik Levy chair. The idea was to split and bend wood to two or more different sides.

That was your idea?

Yes. One thing you, as a designer, must know to do well is to see things. Observation is a powerful tool. Splitting wood was and, at the same time, wasn’t new. A lot of people have tried to do something similar, but they’re only pretending; they use glue and such. When I uttered the word “split”, it caused a bit of an earthquake. But everyone liked it and Milan decided we would try it. I wanted the bending to two different sides to be functional so that it wouldn’t be only a decorative element, though the chair is beautiful even from below.

You also chose to use a colour gradient, which is unusual for a painted chair.

That was another shock. What colour would I imagine? So I told them that I wanted a gradient, like on surfboards. They wondered if I was crazy. So I showed them. I took a spray gun that I used for painting boards and I nicely painted the chair. The guy who had been painting chairs at TON until then became an artist from that moment. He surely went home and told his wife that it was fantastic.

Do you go to IKEA stores?

I love IKEA; it’s a star.

Do you have anything from IKEA at home?

Of course. They work for the deciding masses, so they can manufacture a range of excellent, high-quality items for an affordable price. Designers find themselves in the paradoxical situation that they can’t afford to buy their own work. For example, I’ll design a sofa for Molteni, but I can’t go to a shop and buy it for six thousand euros. They are beautifully made things. But I’m glad when, for example, a lamp I designed cost two hundred euros. Design is democratic. It bothers me that they copy at IKEA, or let’s say they are strongly influenced.

Are they influenced in anything by your work?

I rather see a trend. Suddenly wire is commonly used, furniture made of wire, similar to what I did for Zanotta, but it wasn’t only at IKEA, which has been very powerful for a number of years and influences people’s taste. It is perfect in how it designs and equips kitchens for customers. Their plastic chairs cost seven euros, while a similar plastic chair from Majis costs two hundred and fifty, whereas design is irrelevant in the case of a plastic chair that costs seven euros. IKEA should have its own stand at the trade fair in Milan, just to slap everyone in the face with that. IKEA also sells a lot of rubbish, some things that people shouldn’t buy, such as glass. But they made excellent flatware in their time. They also used to be strong in producing high-quality light fixtures, but everyone can manufacture in China. “The name doesn’t make the product. It’s the product that makes the name. If you put the name on a bad product, it still won’t sell.”

Arik Levy (52)

Designer, artist, photographer and filmmaker. Arik Levy was born in Israel and was involved in surfing, sculpting and graphic design during his childhood and adolescence. At the age of 28, he departed to Switzerland, where he studied industrial design at the Art Centre Europe in La Tour-de-Peilz. He later moved to Paris, where he still lives and is a partner in the L Design studio. His artworks are displayed in most prestigious galleries and museums, while he is a highly respected industrial designer in the portfolios of companies around the world; he is known especially for his work in designing furniture and light fixtures. Firms with which he has collaborated include, for example, Vitra, Visplay, Ligne Rose, Desalto, ic-berlin, Balleri, Italia, Dietiker, Magis, Seralunga, Ansorg, Belux, La Fayette, Lampert, Vibia and, in the Czech Republic, Lasvit, Bomma and TON. For the Atomium in Brussels, he created the celebrated eight-metre RockGrowth 808 Atomium sculpture, which draws from Levy’s longstanding interest in the formation of stones and crystals. He has three children.

Text: Nora Grundová

Photos: David Neff